1. What Is Strategic Transaction Value (and When Does It Matter)?

Table of Contents

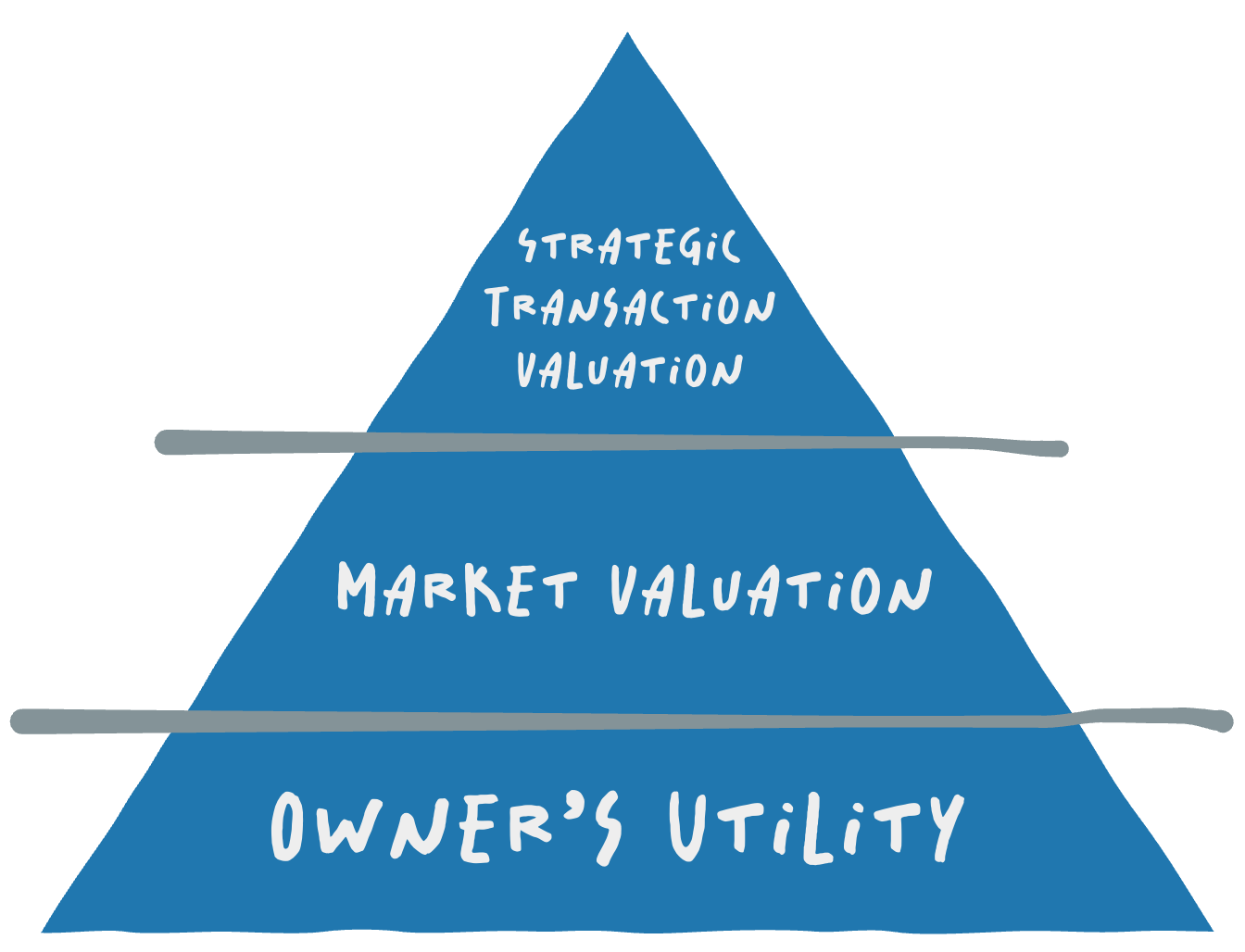

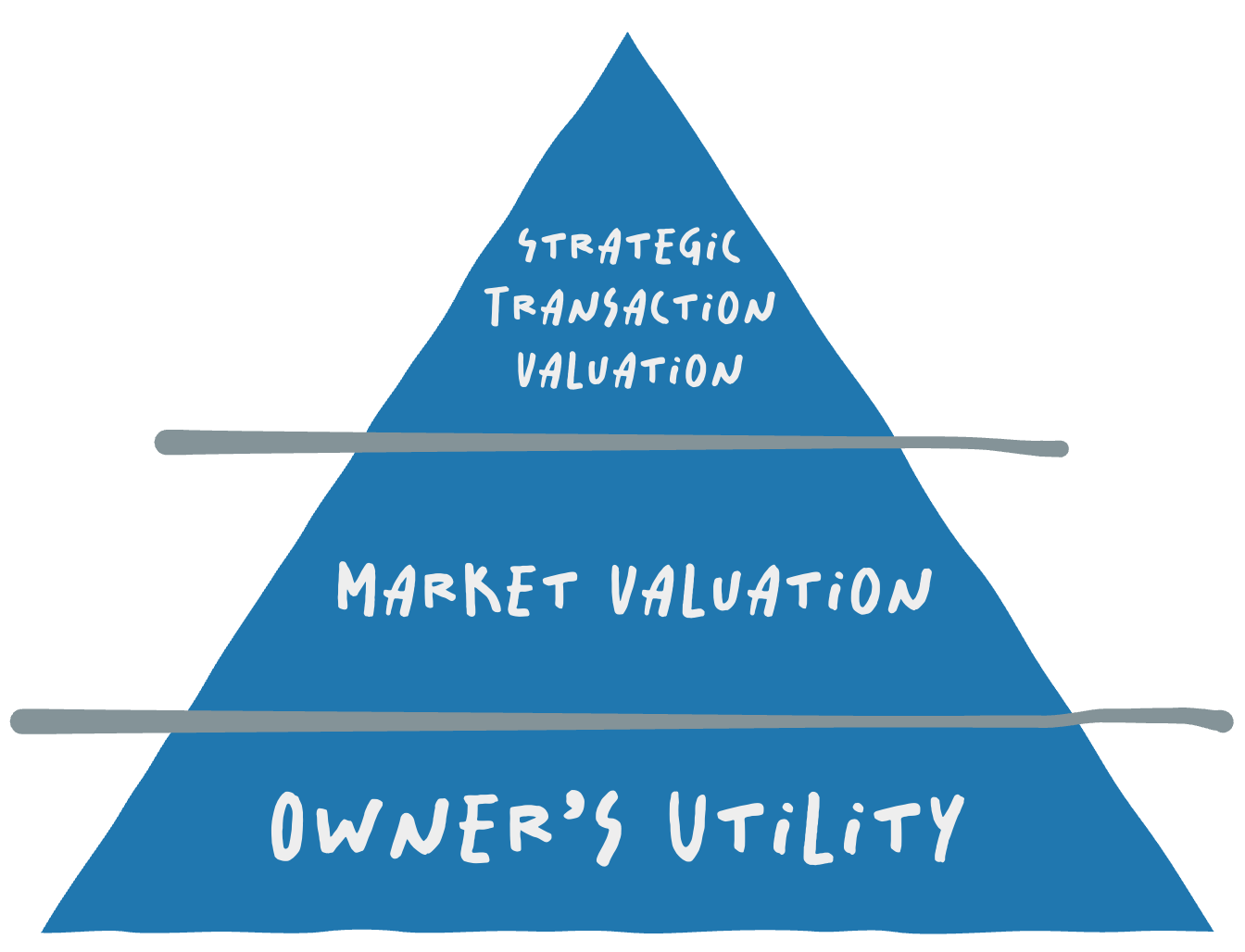

Up until now, we’ve been focused on understanding value through the lens of your goals

Owner’s Utility Value: What is this business worth to you based on your time, income, and wealth goals.

Market Valuation Lens: What your business be worth on the open market, based on the four KPIs, normalized EBITDA, a market multiple, net debt and your normalized working capital.

But there’s a third layer to the pyramid, and it only comes into focus when an actual deal is on the table.

That’s what Lens 3 is for:

Strategic Transaction Value is what your company is worth to a specific buyer, in a specific deal, at a specific moment in time.

It stacks on top of Lenses 1 and 2—not as a replacement, but as an overlay. You can’t understand the strategic value of a transaction without knowing:

What your business is worth to you (your Owner’s Utility Value),

What it’s worth to the market (cash-free, debt-free value based on the four KPIs),

And what it’s worth to them (the strategic buyer, based on their goals, constraints, and deal structure).

Without this third lens, owners often default to two extremes:

They overvalue the business emotionally (“It’s worth whatever I want to get.”)

Or they anchor to a market-based multiple (“We’ve got $3M in EBITDA, and these companies sell for 5×.”)

Both are incomplete. Neither reflects what’s actually going to show up on a term sheet.

Because here’s the truth:

No one buys your business “in general.”

They buy it in a specific way, for a specific reason, to achieve a specific goal.

That goal could be financial, strategic, operational, or all three.

And depending on who they are, what their capital looks like, and how they plan to run the business after closing, the deal value to you could swing by millions.

When Does The Strategic Transaction Value Come Into Play?

This lens activates the moment someone shows real interest in your business and a deal starts to form.

Whether it’s a friendly conversation with a peer, a cold call from a PE firm, or a banker teasing offers from multiple parties, you’ve now entered the zone where decisions get real, pressure ramps up, and clarity becomes crucial.

You are no longer just “worth 6× EBITDA.”

You’re negotiating a one-of-a-kind transaction.

At this point, value becomes dynamic. It depends on:

Who the buyer is

Why they want the business

What return they need

What deal structure they offer

What role they want you to play (or not play)

And what risks and upsides they’re underwriting in their model

This is where owners get taken advantage of or they step into the arena ready to go.

The Goal of Lens 3 - Strategic Transaction Value

The purpose of Lens 3 isn’t to make you a deal junkie or prep you to sell.

It’s to give you a framework to evaluate offers, understand trade-offs, and navigate conversations with confidence—even if you decide not to sell at all.

In this section, we’re going to walk through:

The six primary ownership structures behind every buyer

The common types of buyers in the private market (and how they behave)

The deal structures that shape how the purchase price turns into real money

How to evaluate all of that through your personal goals for time, cash, and wealth

When you can see the transaction through all three lenses—utility, market, and strategic—you stop reacting to noise and start negotiating like a true capital allocator.

2. How to Stack the Three Valuation Lenses

Most owners only look at a business through one lens, if any.

And even then, the view is often distorted by gut feel, bank statements, or someone else’s opinion.

But when real money, roles, and relationships are on the line, clarity matters.

That’s why the Strategic Transaction Value sits at the top of the pyramid, stacked on top of the two lenses that come before it.

Let’s walk through each one.

Lens 1: Owner’s Utility Value — What the Business Is Worth to You

This is the foundational lens.

It asks: What does this business do for my life today, and what could it do for me tomorrow?

Owner’s Utility isn’t about market price or outside opinions. It’s about how the business serves your personal goals for:

Time — Your role, identity, and freedom

Cash Flow — How much income you take home and how consistently

Wealth — Your long-term equity value and optionality

This lens puts you in the driver’s seat. It helps you stop chasing growth blindly or getting distracted by “valuation.” You’re not optimizing for vanity metrics. You’re designing your business to serve your life.

Lens 2: Market Valuation — What the Business Is Worth to the Market

This lens strips away emotions and personal context, replacing them with real math.

It asks: What would this business likely be worth in a clean, arms-length transaction, assuming no premiums or strategic buyers?

The Market Valuation Lens is grounded in four KPIs:

Normalized EBITDA — Clean, adjusted proxy for operating cash flow

Valuation Multiple — Market shorthand for risk

Net Debt — Total debt minus excess cash

Normalized Working Capital — The engine that keeps the business running

Together, these form the baseline value of your business in the market, regardless of who owns it.

It’s your “par value.” The $3 bottle of water in the city.

This lens helps you run the business more intentionally, like an investor, not just for income, but for asset growth.

But as powerful as this lens is, it’s incomplete on its own.

Lens 3: Strategic Transaction Value — What the Business Is Worth to a Specific Buyer

Now we’re in deal territory.

This lens asks: What would a specific buyer be willing to pay, and what would the deal actually mean to me—financially, operationally, emotionally?

This is where the real nuances take place.

Because strategic transaction value is not just about your business, it’s about the buyer’s goals and access to capital.

A buyer’s offer depends on:

Their ownership structure and return targets

Their reason for acquiring you (strategy, synergies, financials)

Their desired role for you post-close

Their timeline, sources of capital, cost of capital, and risk profile

The specific deal structure they use to transfer the purchase price

This is the $3,000 bottle of water in the desert.

Same core business, but the value has context and will be negotiable.

Why You Need All Three

When you view your business through all three lenses, you stop flying blind.

You can see:

How your business supports your life (Lens 1)

How it performs in the open market (Lens 2)

How it fits into someone else’s strategy (Lens 3)

This clarity gives you leverage. It lets you compare a deal against your current reality.

You can say: “Is this deal actually better than what I already have?”

It’s the difference between getting swept up in momentum…

Or walking into a transaction with your eyes wide open, confident you’re making the right move for the right reasons.

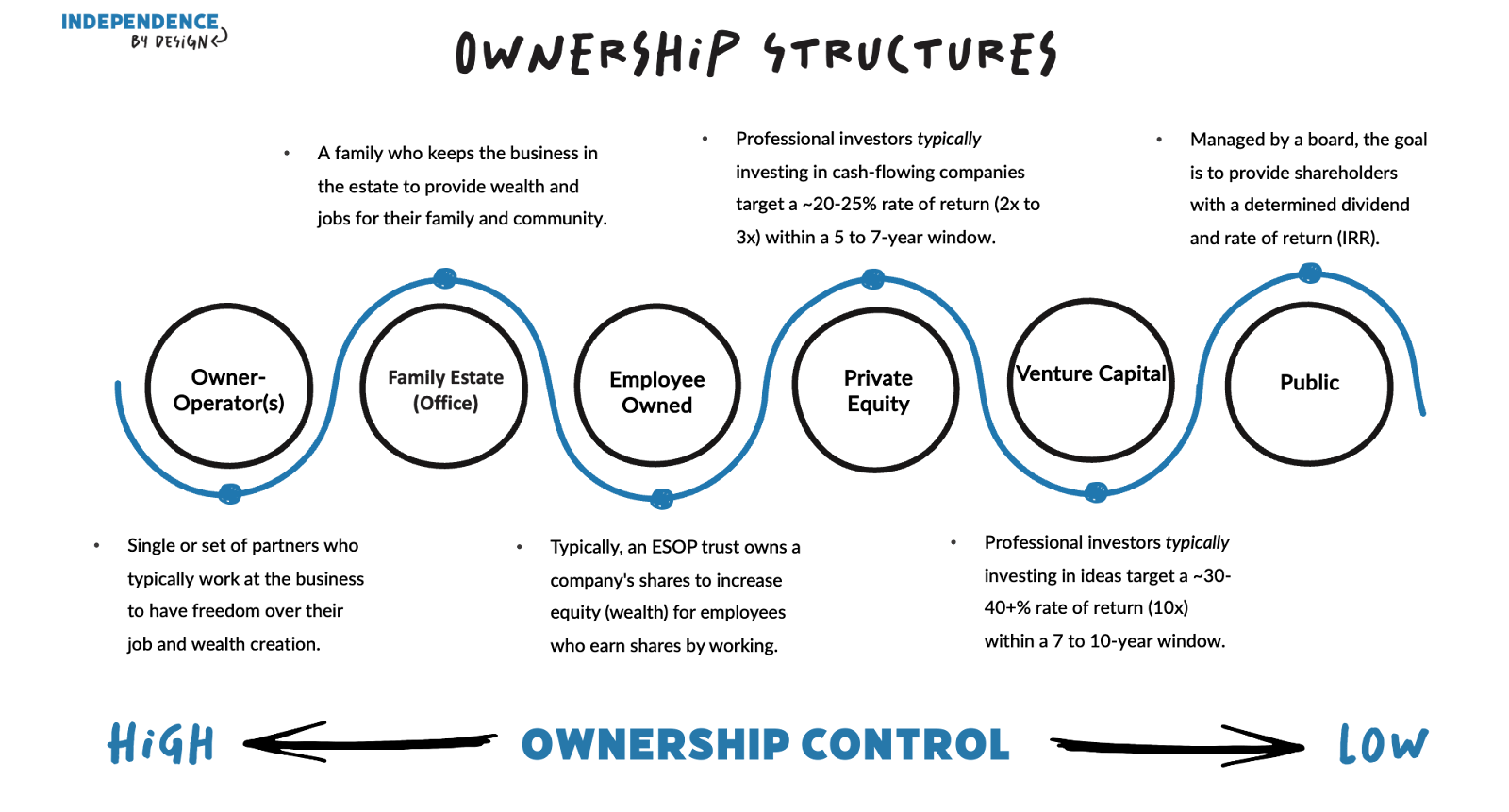

3. The Six Ownership Structures That Drive Strategic Value

When most owners think about a “buyer,” they picture a person.

A CEO. A private equity firm. A competitor down the street.

But behind every buyer is an ownership structure, and that’s where the real strategic drivers come from.

The ownership structure determines:

What kind of returns the buyer needs

How fast they need them

How they’ll finance the deal

What role they want you to play (or not)

What happens to your company after the deal closes

You’re not just negotiating with a person.

You’re aligning with an investment thesis, whether you know it or not.

So before we talk about specific types of buyers, we need to understand the six main ownership structures that shape how value is created and measured after a deal.

1. Owner-Operator (Privately Held)

Primary Objective: Time, cash flow, wealth and control for the individual owner

Return Target: Depends on personal risk tolerance and goals

Timeline: Often indefinite or lifestyle-driven

This is the most common structure in the middle market: one or more individuals who own and run the business themselves. They may be entrepreneurs, family members, or internal teams buying into or out of the business.

It’s driven by their Owner’s Utility (Lens 1). They care about control, income, flexibility, and long-term sustainability and wealth. Some will optimize for cash flow and distributions; others for growth and equity value. Their “IRR” is often personal, driven by what the business provides for their life.

2. Family Office

Primary Objective: Long-term wealth preservation for a family or group

Return Target: 10–15% IRR over long holding periods

Timeline: Often 10+ years; patient capital

Family offices invest directly in private companies as a means of building and preserving wealth. They back the management team and look for stable, cash-flowing companies that they can hold for the long term.

They’re less likely to flip a company in 5 years and more likely to focus on stewardship, governance, and sustainable growth. That can make them attractive partners for owners who care about long-term impact and cultural continuity.

3. Employee-Owned (ESOPs and Variants)

Primary Objective: Transition ownership to employees

Return Target: Long-term wealth creation for the employees

Timeline: Long-term internal succession driven

ESOPs (Employee Stock Ownership Plans) allow owners to sell all or part of the company to employees, typically through a trust structure.

They’re a pure ownership transition, not a strategic or operational one. That means you need strong management in place, clear financials, and a sustainable business model before you can step back from your role. ESOPs offer liquidity without selling to outsiders and often protect the company’s legacy.

4. Private Equity

Primary Objective: Maximize IRR for fund investors

Return Target: 20–30%+ IRR over a 3–7 year hold

Timeline: Short to medium term

PE firms raise capital from institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals, then acquire companies to grow and exit them at a profit.

They buy with a specific thesis, either as a platform (the base company) or a bolt-on (an add-on to an existing platform). Their goal is to increase EBITDA, expand the multiple, and exit at a premium.

They’re financially driven, operationally involved, and focused on execution. That can be great, or overwhelming, depending on what you want next.

5. Venture Capital

Primary Objective: Hypergrowth and massive upside

Return Target: 10x+ returns, hoping one out of twenty bets work out

Timeline: 5–10 years, with high failure tolerance

VCs don’t buy companies, they invest in early-stage businesses with great ideas and high growth potential. While not typical buyers for owner-operated firms, it’s still worth noting their model.

They care about scalability, market size, and speed. Their capital comes with expectations: fast decisions, frequent capital raises, and a clear exit (usually IPO or acquisition).

6. Public Company

Primary Objective: Shareholder returns and strategic advantage

Return Target: Earnings Per Share (E/P) growth and shareholder value

Timeline: Ongoing, but quarterly performance pressure

A public deploys shareholder capital to drive growth, expand offerings, or gain market share.

Their decisions are governed by board approval, quarterly earnings calls, and strategic priorities. These buyers often have well-oiled integration teams and may eliminate your need to stay on post-close—if that’s what you want.

Why These Structures Matter

Each ownership structure has different timelines, strategies, operational influence, and goals for cash flow and the liquidity of their equity. The ownership structure impacts how a company is managed and can give you insight to what it may be like working in, or selling to, each structure.

When you sell, not just selling to a person.

You’re partnering—or parting ways—with an entire system.

That system has:

A reason for buying you

A timeline for achieving returns

A structure for managing the company

A philosophy for what happens post-close

Understanding who’s behind the offer helps you:

Anticipate their strategy

Clarify their expectations

Evaluate whether your goals align

Avoid surprises after the handshake

Because one offer might give you a clean exit with no strings attached.

Another might require you to stay on for five years, hit an earnout, and deal with reporting to a board.

Next up, we’ll break down the six primary ownership structures that sit behind most buyers—and why understanding their goals is the key to making sense of any offer.

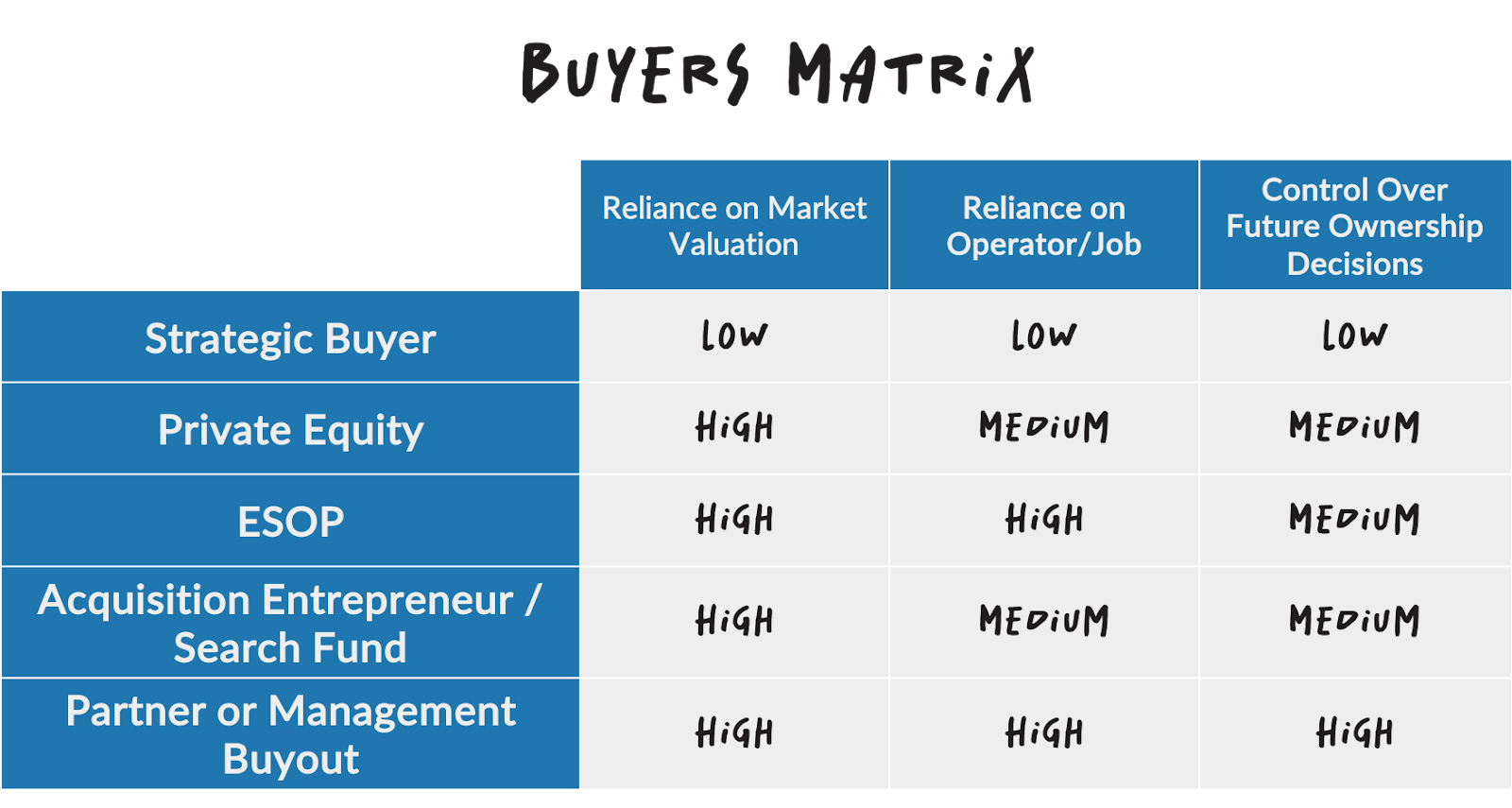

4. The Five Buyer Types You’ll Actually Encounter

Ownership structure tells you how a buyer thinks.

But buyer type tells you who is actually coming to the table, and what that means for your deal.

In the real world of privately held companies, most owners won’t be dealing with venture capitalists or public companies. You’re far more likely to get approached by one of these four:

Strategic Buyers

Private Equity Firms

Employee Ownership Buyers

Acquisition Entrepreneurs / Search Funds

Partner or Management Buyouts

Each of these buyer types has different motivations, capabilities, timelines, and implications for your role, your team, and your future.

Let’s break them down.

1. Strategic Buyers

Who they are:

Other companies (private or public) who want to buy your business to accelerate their own growth plan.

What they care about:

Every company has their own cash flow and valuation targets, which depend on the ownership structure. Strategice buyers want to accelerate their own plan through revenue synergies, cost savings, strategic fit, people, customer relationships, capabilities, or geographic footprint.

How they approach valuation:

They start with the same four KPIs we outlined in Lens 2—normalized EBITDA, market multiple, net debt, and working capital. But they’re willing to pay more than “market” if your business fills a critical gap or accelerates a core initiative.

What it means for you:

May offer a premium over market value

Often don’t need you to stay on long-term

May integrate your team or systems into their own

Culture and legacy can change fast

Key question to ask:

“Why is this business worth more to them than to anyone else?”

2. Private Equity Firms

Who they are:

Financial buyers who acquire companies to grow and sell them at a profit, usually within 3–7 years.

Two roles you might play in their strategy:

Platform company: You’re the anchor investment they’ll grow around. All focus is on your four KPIs, leadership team, and operational readiness.

Bolt-on acquisition: You’re an add-on to a company they already own. Value depends on how you fit into the broader platform (customers, region, capabilities, etc.).

How they approach valuation:

Platform: Market-based based on the four KPIs, normalized EBITDA, multiple, net debt, and normalized working capital.

Bolt-on: This looks a lot like a Strategic Buyer, they may pay a premium (but they are often smaller companies at a lower value) based on synergy or strategic leverage with the goal of increasing their market valuation.

What it means for you:

May ask you to stay on for 1–3 years

Will want detailed financials, systems, and clear roles

May bring professional management, board meetings, reporting

Roll equity is common, giving you a second bite at the apple

Key question to ask:

“Am I the investment… or just part of it?”

3. Employee Ownership Buyers

Who they are:

Internal transitions occur when your company is owned by your team through a trust, typically via an ESOP (Employee Stock Ownership Plan).

What they care about:

Stability, sustainability, cultural continuity, and alignment with employee values. ESOPs are not looking to flip the business; they’re looking to grow long-term value for the beneficiaries of the trust (the employees).

How they approach valuation:

They start with the same four KPIs we outlined in Lens 2—normalized EBITDA, market multiple, net debt, and working capital. Premiums are less common; however, there are significant tax advantages for the seller and the new ownership structure, and the deal is often cleaner and culturally aligned.

What it means for you:

You’ll need a strong leadership team and a succession plan for your role

Often tax-advantaged and emotionally rewarding

Can be slower or more complex to structure

You may stay involved to guide the transition

Key question to ask:

“Am I solving for control, culture, and continuity—or for cash?”

4. Acquisition Entrepreneurs / Search Funds

Who they are:

Independent individuals (or small teams) who raise capital from investors or use SBA loans to buy and operate a company themselves.

What they care about:

Buying a business they can run. Often first-time CEOs with investor backing or SBA financing. They want a profitable, stable business with potential to grow.

How they approach valuation:

Very disciplined. Cash flow matters most. They’re not paying strategic premiums—they need to service debt, pay investors, and still make a return.

What it means for you:

They’ll likely want you to help during the transition

May bring fresh energy and hunger, but often limited experience

Great option if you want out of the role, but care about the team

Bank financing or seller financing may be involved

Key question to ask:

“Is this person ready to run what I’ve built?”

5. Partner or Management Buyouts

Who they are:

Key people already inside the business—partners, minority shareholders, or senior leaders—who want to buy out the existing owner to take full control. Sometimes it’s a formal management team. Other times, it’s a single person who’s been groomed over time.

What they care about:

They already know the business. They’ve lived the culture. They care about continuity—for the team, the clients, and themselves. Most management or partner buyouts happen when there’s trust, aligned values, and a desire to avoid an outside sale.

How they approach valuation:

The four KPIs still matter—Normalized EBITDA, Multiple, Net Debt, and Working Capital—but there’s usually a practical ceiling on price. The number must be affordable based on the company’s existing cash flow.

What it means for you:

Great fit if you want a quieter, more discreet transition

You’ll need to assess leadership readiness and build guardrails around the role shift

There’s often a period of mentorship or phased transition

Deal structure is key: expectations must be crystal clear to avoid resentment

The valuation may be lower than a third-party strategic, but the cultural continuity and clean handoff often make it worth it

Key question to ask:

“Is this person ready to own—not just run—this business?”

Summary: Buyer Type Shapes the Deal

Every buyer starts with the same four KPIs from Lens 2.

But how they see those numbers—and what they’re willing to do with them—depends entirely on who they are and how they’re funded.

That’s why strategic transaction value is not just about what the business is “worth.”

It’s about who’s buying, why they’re buying, and what happens next.

Each of these buyer types comes with different:

Roles for you post-close

Cash flow implications

Deal structures

Cultural and operational transitions

Understanding the type of buyer helps you evaluate:

Whether your goals align

What tradeoffs you’re being asked to make

Whether the offer really gets you closer to what you want

Up next, we’ll walk through how each of these buyers uses deal structure to shape return profiles and get the deal done, without changing the headline price.

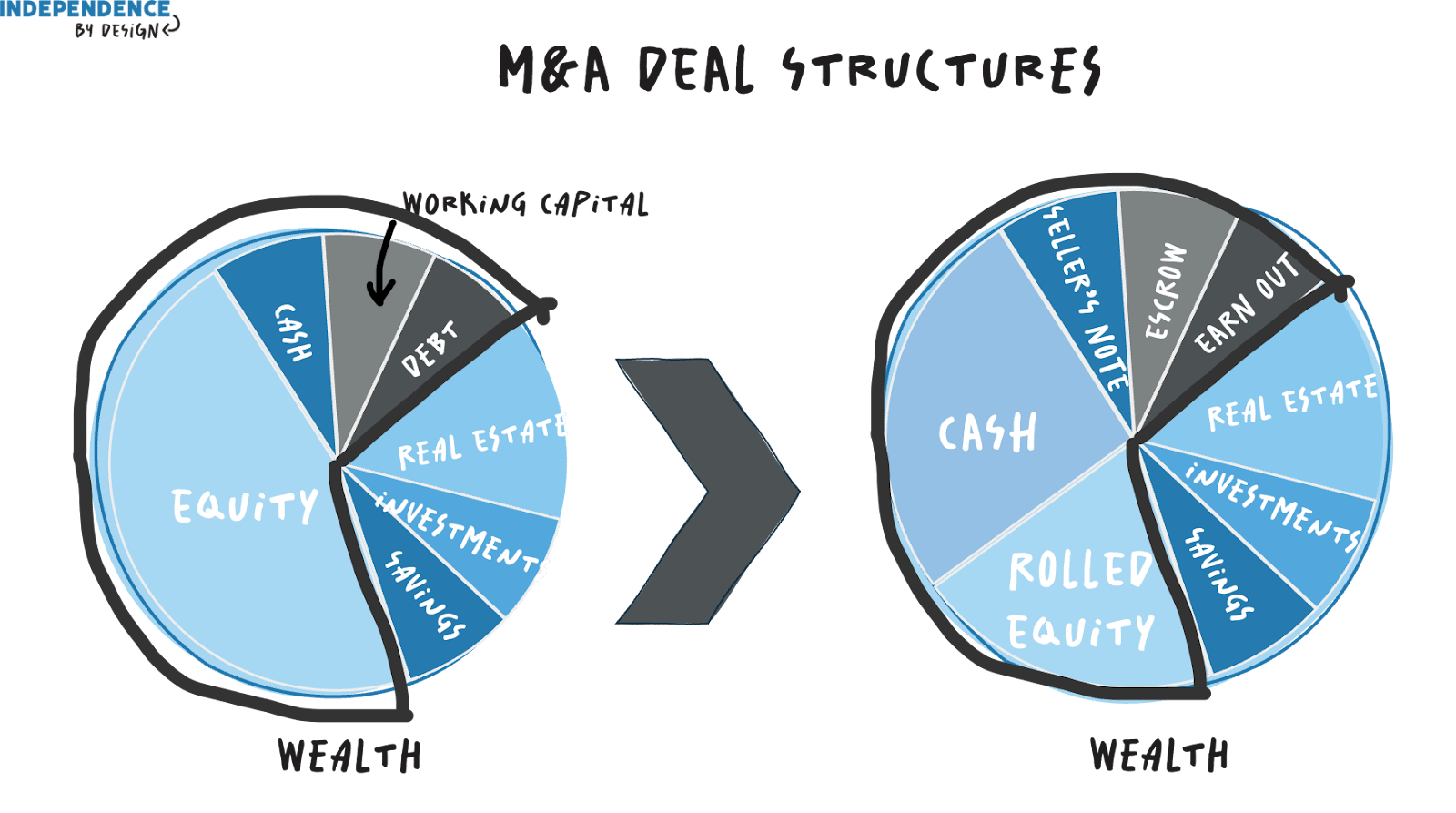

5. The Six Deal Structure Levers

Every buyer has a price they are willing to pay. A number they float out in a term sheet..

But how they deliver that number, and what it actually means for you, is shaped by deal structure.

Two deals can have the exact same purchase price… and result in wildly different outcomes for the seller.

That’s because price is just the beginning. The real questions are:

How much do you get up front?

How much is deferred?

What strings are attached?

How much risk are you still carrying?

This is where deal structure comes in.

The Purchase Price Is Not the Payout

You might get a $10 million offer. But that doesn’t mean you walk away with $10 million at close. The actual payout depends on how the purchase price is structured.

And deal structure is how buyers reconcile three things:

Their investment strategy (return expectations, time horizon, risk tolerance)

The quality of your business (how confident they are in your four KPIs)

Your post-close role and involvement

The more risk the buyer perceives, the more they will leverage the deal structure as a means of mitigating risk and increasing their chances of achieving their returns. The stronger your company’s performance and transferability, the more leverage you have.

Here are the six most common deal structure levers used in private company transactions:

1. Cash at Close

What it is:

The portion of the purchase price paid to you at closing, in cash.

Why it matters:

It’s the cleanest, least risky part of the deal. The more cash you receive up front, the more certainty you have.

Typical range:

The range is vast and depends on the buyer, their perceived risk, and access to capital.

Watch for:

Cash being reduced to cover working capital or debt surprises

Cash being allocated to escrow due to perceived risk (more on that below)

Tax implications tied to how cash is categorized in the deal

2. Seller’s Note

What it is:

A promissory note where you act as the lender. The buyer pays you back over time, with interest.

Why it matters:

It bridges the gap between buyer and seller expectations. You get more total value, but take on credit risk.

Terms to negotiate:

Interest rate

Duration

Collateral

Personal guarantees (if any)

Used when:

Buyer needs to reduce cash outlay

Buyer wants alignment or support post-close

Bank financing needs to be layered with seller flexibility

3. Earnout

What it is:

A contingent payout tied to the business hitting certain operational performance milestones post-close.

Why it matters:

Earnouts are often used when the buyer isn’t fully confident in your growth forecast, but is willing to pay more if it works.

Typical triggers:

Revenue targets

EBITDA thresholds

Key customer retention or contract renewals

Risks:

You no longer control the business

Targets can be manipulated or missed

It becomes a legal and emotional minefield if not clearly defined

4. Escrow / Holdback

What it is:

A portion of the sale proceeds is held by a third party (escrow agent) to cover potential liabilities, indemnities, or post-close disputes.

Why it matters:

It protects the buyer, but also delays your full payout.

Typical range:

5%–15% of the purchase price, held for 12–24 months.

You get it back if:

There are no material breaches

All agreed-upon milestones or warranties are met

5. Rolled Equity

What it is:

You “roll” a portion of your proceeds into equity in the new entity, essentially reinvesting alongside the buyer.

Why it matters:

It gives you a second bite at the apple. If the new entity grows and sells again, you benefit from the upside.

Common in:

Private equity deals

Management buyouts

Growth-focused acquisitions

Tradeoffs:

Less cash now, potential for more later

No control over future exit

Depends entirely on buyer execution

6. Net Proceeds: The Real Number That Hits Your Bank Account

Normalized EBITDA × Multiple = Enterprise Value

– Net Debt

– Normalized Working Capital

= Equity Value

– Taxes, Fees, Phantom Equity

= Net Proceeds

Once you understand the value of your business in the eyes of a buyer and the deal structure on the table, you still need one final lens:

What money actually hits your bank account, and when?

That’s where net proceeds come in. This is the final, real number that determines whether the deal supports your time, cash flow, and wealth goals — or not.

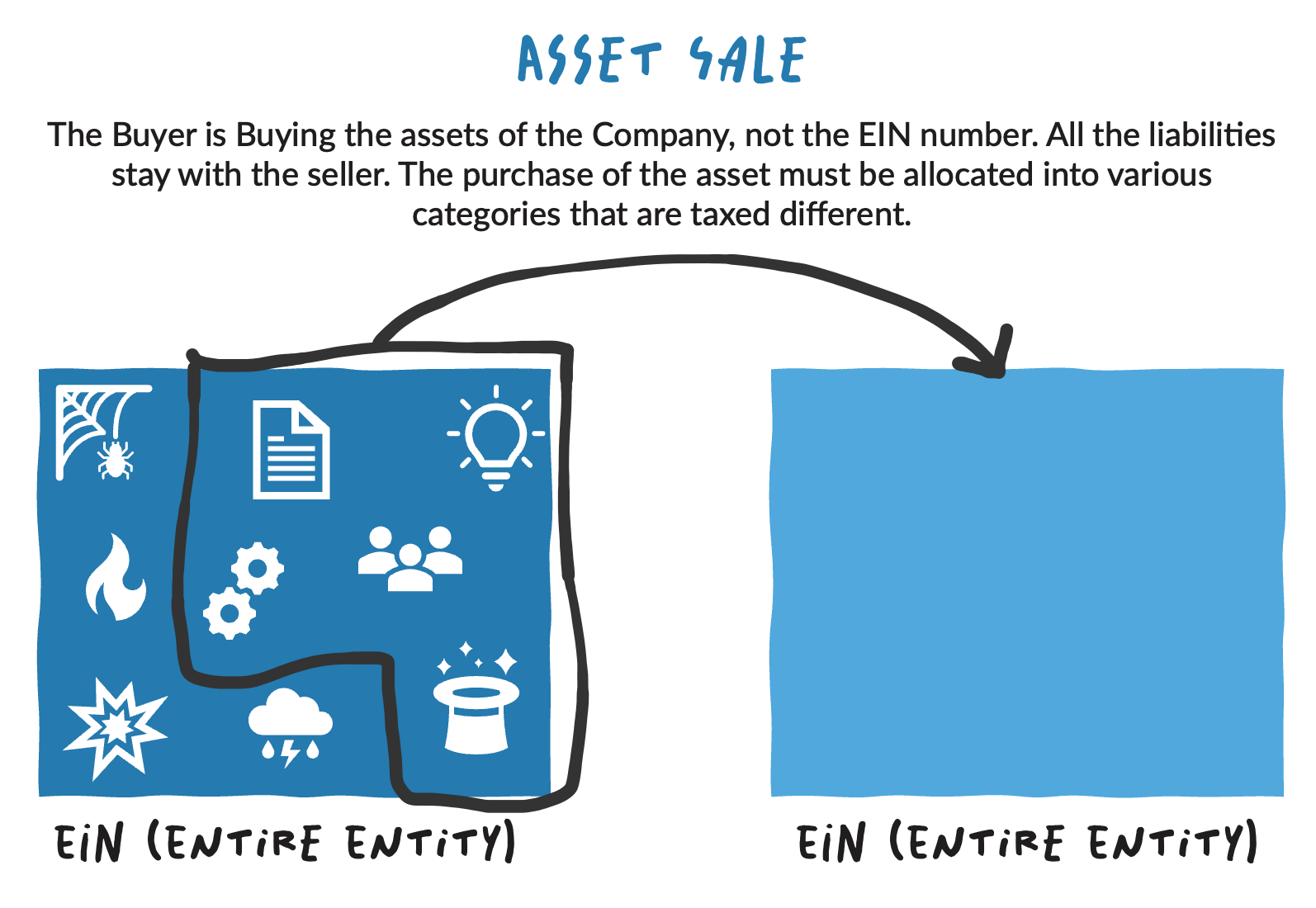

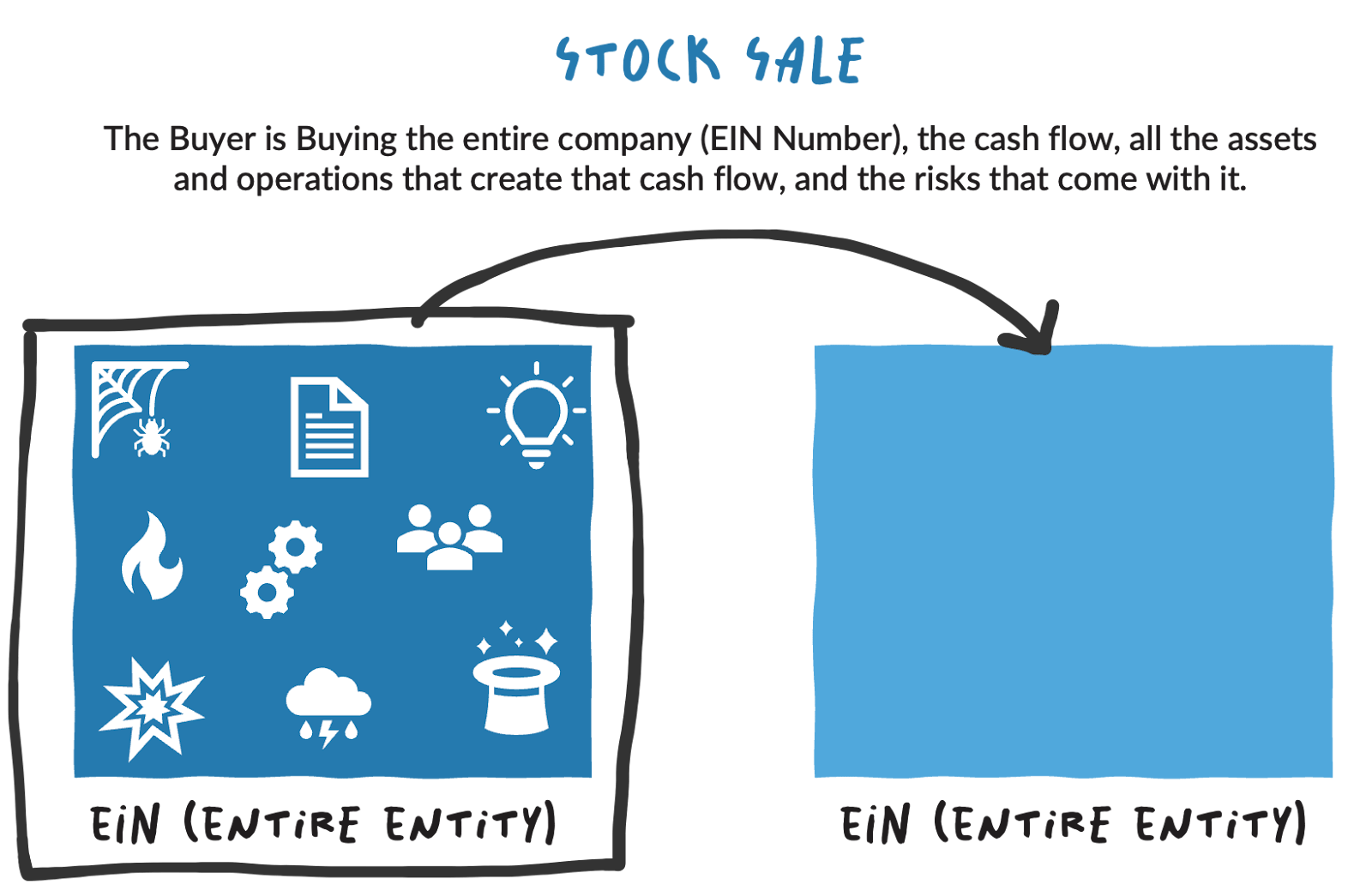

A. Asset Sale vs. Stock Sale: The First Fork in the Road

This is one of the biggest drivers of your tax outcome. This is often the first point of contention.

In an asset sale, the buyer purchases the assets of the company, not the entity itself. The EIN stays with you, and the assets are split into IRS-defined buckets: goodwill, fixed assets, inventory, non-competes, consulting, etc. Each bucket is taxed differently, some at capital gains rates, others at ordinary income.

In a stock sale, the buyer purchases the shares or membership interests of the company itself. The EIN and all liabilities transfer. This structure is simpler and usually results in more of the proceeds being taxed at favorable long-term capital gains rates.

Why does this matter?

Because buyers prefer asset sales, they get a stepped-up basis for depreciation and shield themselves from historical liabilities.

Sellers, on the other hand, prefer stock sales; they simplify the transaction and optimize for capital gains.

This tug-of-war has massive implications:

Depreciation recapture in an asset sale could spike your tax bill

The structure will determine whether you're paying 20–30% or 40–50% in effective taxes

You might not have a choice depending on the buyer type (PE vs. strategic) or entity structure (S-Corp vs. C-Corp)

This is why modeling your net proceeds is non-negotiable. The same purchase price could result in wildly different outcomes depending on how the deal is structured.

B. Tax Treatment of Each Deal Component

Even beyond the asset vs. stock decision, each part of the deal has its own tax implications:

Deal Component | Typical Tax Treatment |

Cash at Close | Capital gains (stock sale) or mix of capital gains and ordinary income (asset sale) |

Seller Note (P&I) | Interest taxed as ordinary income |

Earnout | Usually taxed as ordinary income |

Escrow/Holdback | Typically taxed as capital gains, with timing nuance |

Rolled Equity | No tax due at time of transaction (deferred) — but no guarantee of liquidity |

The takeaway: Not all dollars are created equal. Getting $2M as cash at close isn’t the same as getting $2M in an earnout over five years taxed at ordinary income rates.

The timing, risk, and tax treatment of each part of the deal must be weighed carefully.

C. Fees and Carve-Outs That Erode the Headline Number

In addition to taxes, you need to account for the fees and obligations that reduce your take-home amount.

Here’s what typically gets carved out of the equity value:

Business Broker or M&A Advisor: 5%–10% of the transaction price

Investment Banker: 1.5%–4%, often tiered by size of deal

Legal Fees: $50k–$250k+, depending on complexity

Tax and Accounting Advisors: $25k–$100k+

Other Consultants: IT, HR, comp advisors, diligence support

Phantom Stock or Employee Bonuses: often 5%–15% of the deal if you’ve promised team-based upside

These can add up quickly. On a $10M deal, fees and carve-outs might total $500k–$1.5M — before taxes.

If you haven’t modeled them, you’re going to have a rude awakening.

7. Net Proceeds: Example

Let’s bring everything together.

Say you receive a $10 million enterprise value offer for your company. Sounds great, right? But what you actually keep—after taxes, fees, and deal structure terms—is a different story.

This is where the Net Proceeds Calculator becomes essential. Because what you walk away with depends on:

How the deal is structured

How each component is taxed

What’s deferred, at risk, or contingent

When and how the money shows up

And how it all lines up with your personal goals

Assumptions

Enterprise Value: $10,000,000

Normalized EBITDA: $1,666,667

Multiple: 6×

Net Debt: $1,000,000

Working Capital: $500,000

Equity Value = $10M – $1M (net debt) = $9M

Working capital is not subtracted here. A normalized working capital target is set in the LOI, and the final purchase price is adjusted up or down based on how much you actually deliver at close.

Deal Structure:

60% Cash at Closing ($5.1M)

20% Seller Note ($1.7M)

10% Earnout ($850K)

10% Rolled Equity ($850K → $1.7M by year 6)

Deal Fees:

5% of EV = $500,000

Taxes:

Capital Gains (CG): 20%

Ordinary Income (OI): 37%

Seller Note Interest: 8% annual, 5-year term

Earnout Paid Over: 3 years

Net Proceeds Waterfall (After Taxes & Fees)

Year | Component | Amount | Tax Rate | After-Tax Proceeds |

1 | Cash at Closing (60%) | $5,100,000 | 20% CG | $4,080,000 |

1 | Deal Fees | –$500,000 | – | –$500,000 |

1–5 | Seller Note Interest | $680,000 | 37% OI | $428,400 |

2–4 | Earnout (⅓ per year) | $850,000 | 20% CG | $680,000 |

6 | Seller Note Principal | $1,700,000 | 20% CG | $1,360,000 |

6 | Rolled Equity Exit | $1,700,000 | 20% CG | $1,360,000 |

Total Proceeds | $7,908,400 |

What This Reveals

The headline number isn’t the number that matters. $10M EV turns into ~$7.9M in post-tax cash flow—spread over 6 years, with ~40% of it tied up in risk, time, and contingencies.

Each component has a different level of risk and tax treatment:

Cash at close is the cleanest—but only 48% of the full deal after fees and taxes.

Seller notes earn interest, but you’re acting like a bank—and interest is taxed as ordinary income.

Earnouts are performance-based, meaning you could miss them entirely.

Rolled equity is a bet on the buyer’s exit plan—and you don’t control the outcome.

Your deal structure determines your lifestyle runway.

Can you live off $4M from year one? Or are you depending on the seller note, earnout, and equity exit to hit your targets?

The Risk-Adjusted View

Here’s what an experienced investment banker will tell you: You should never assume you’ll get 100% of the paper deal.

In fact, here’s a typical probability-weighted view of the more uncertain components:

Component | Probability | After-Tax Value | Adjusted Proceeds |

Earnout | 50% | $680,000 | $340,000 |

Seller Note (P+I) | 90% | $1,788,400 | $1,609,560 |

Rolled Equity | 60% | $1,360,000 | $816,000 |

Total Risk Adj. | $6,765,560 |

If things go sideways—market downturn, buyer mismanagement, earnout miss—you could be looking at a nearly $1.2M gap compared to your modeled outcome.

That’s why we don’t just look at EV.

We build waterfalls. We model scenarios. We make decisions aligned with personal goals and downside protection.

The Bottom Line

Your enterprise value is not your exit value.

Deal structure is not just a negotiation tool—it’s a risk allocation mechanism.

Without modeling net proceeds, you’re flying blind.

By building a clear, honest net proceeds model, you step into the boardroom like an investor.

You stop chasing vanity valuations and start optimizing for your actual life.

This is the final lens of Strategic Transaction Value.

It forces the real question:

“What am I actually trading… and what am I getting in return?”

6. Conclusion: Valuation Clarity Is Ownership Power

Valuation isn’t a single number. It’s a lens to help your run your business from the boardroom.

When you understand the three lenses—Utility, Market, and Strategic—you gain a toolset that goes far beyond selling your business. You get a framework to:

Run your company like an investor

Make confident decisions about time, cash, and wealth

Filter noise and know when an offer is real

Align with the right buyers on your terms

Avoid regret—and negotiate with clarity

This isn’t just about preparing for a sale.

It’s about building a company that supports your life, on your terms.

You may never sell.

You may sell in five years.

Or you may get an offer tomorrow that you didn’t see coming.

But no matter what path you take, clarity is power.

Use these lenses to own your narrative, protect what you’ve built, and make the next chapter—whatever it is—one you choose with full awareness.